Even if it’s true that this photo of the University of Canterbury library shelves tumbled like dominos was by far the worst of the library damage, it’s an image that has stuck in my head these past weeks. Imagine -- as with so much else about the quake -- if it had happened in daylight, on a working day! How many students would have been flattened like so many pressed flowers in a Victorian album?

OK, probably not many. But -- if it’s permissible to indulge in black humour at this stage -- they would have been the diligent ones, yes? A generation of future scholars wiped out at a stroke! What a blow for New Zealand’s intellectual life that would have been.

(I suppose we would need to know the call numbers of those particular shelves to be able to figure out the true intensity of the blow.)

--

When I saw the pictures of what the earthquake had done to the library and to Homebush, I thought of Brancepeth, a historic house in the Wairarapa that was badly damaged in an earthquake in 1917.

“It was the worst I have ever felt,” said Mr H.H. Beetham, of Brancepeth, in reply to a query. Mr Beetham stated that out of about fifteen chimneys at the homestead only three remained intact. The whole of the chimneys in the homes of the station hands were also down. Mr Beetham states that his loss in plate glass, ornaments, etc., was fairly heavy.

Evening Post, XCIV: 32, 7 August 1917, p8 (via Papers Past)

The funny thing was, the grand old house had already been partly demolished and elaborately rebuilt in 1904-1905 (due to its rotting sapwood frame; an elementary mistake on the part of the original builders), and would eventually lose its

restored chimneys to another earthquake in 1942.

Happily, the homestead still stands. And what also survived those various disasters -- and why I was thinking of Brancepeth at all -- was its magnificent lending library, which was established by the Beetham family over the course of several decades from the late 19th C into the early 20th C.

The only reason I know about Brancepeth is from Lydia Wevers’ fascinating new book on the subject: Reading on the Farm: Victorian Fiction and the Colonial World, which (full disclosure) I was lucky enough to help edit.

The two thousand volumes of the Brancepeth lending library, still wrapped in their now-faded red linenette covers, were donated to the Victoria University Library in 1966, where they sit quietly in the original glass cases that were built to hold them. Lydia originally set out to write an essay on the collection as a literary-historical curiosity, and in the course of settling down to work, wrote to the current generation of Beethams to enquire whether the family had any related material lying around.

Did they what! Diaries and letters, yes, but also -- the farm office standing virtually intact from the way it was at the turn of the last century, with the ledgers and account books still sitting dusty and undisturbed on the shelves.

It was a treasure trove for the devoted researcher – which, fortunately for us, is exactly what Lydia is. Anyone else might have glanced at the spidery, minuscule handwriting of the clerk, and put it away as job for some other scholar. Lydia patiently deciphered over a dozen years’ worth of notes about farm business, and in the process discovered, as her book puts it, the “next best thing” to a great New Zealand 19th C novel of manners.

She also discovered a complex, brilliant, and troubled character, in the melancholic person of John Vaughan Miller. He was an educated gent who washed up in the slightly déclassé job of Station Clerk and worked almost without stopping for the 14 years he held the post. Lydia patiently and expertly traces Miller’s story not just via the station diaries, but also through his anonymous annotations in the library books, and his various letters, articles, and other fulminations in the local newspaper, in which he undertook to educate the local populace about crucial matters of the day.

The gap between Miller’s ambitions and his daily life is painfully apparent; likewise the gap between his hard-won learning and the happy leisure of his masters and employers. There are also various feuds and debates and affairs and squabbles and scandals, as well as shopping lists and gardening and visitors and dinners and clothes. The result (and I think it’s all right for me to say this, even though I worked on the book) is a superb example of non-fiction that is almost fictional in its quality and quantity of character and event.

My favourite character, besides Miller, is Willie, the young scion of the Beetham family, whom we meet in Surrey in the early 1850s. Poor self-conscious Willie applies himself with energy but little success to his studies while the family figures out where best to emigrate to. In his diary, Willie laments how pathetic he is at everything; utterly useless at Latin and Greek, too clumsy even to get an apprenticeship with the local blacksmith -- and a really crap diarist, to boot.

But as soon as he boards the sailing ship for New Zealand, something about the salt air invigorates his brain, just as in the best adventure fiction of the day. Within his first couple of years in the new country, Willie goes on to perform feats of engineering to make a blacksmith cry, while also becoming proficient in a language that he never expected to master, and generally advancing the family fortunes. He’s like a walking advertisement for colonialism.

Lydia is careful to remind us just what a pyramid scheme the whole colonial business was, particularly once the early land-grabs were over. The irony is that, like John Vaughan Miller himself, most of the readers on the farm -- the shearers and daggers and shepherds and gardeners and passing homeless swaggers who devoured the colonial romances of patience and pluck rewarded -- would never enjoy the success or wealth of their employers in the big house, who had simply capitalized on their initial luck, good timing, and investments.

That didn’t stop the working men (and likely their wives) from reading and fantasizing about tales of material good fortune, though. One of the delights of Reading on the Farm is how it brings to life those readers and their avid consumption of the best and trashiest fiction of the day. Readers paid the equivalent of a week's wages for an annual membership of the library, and colour plates in the book show some of the best-loved (which is to say, tattered and torn) volumes, their worn covers and their annotations in various hands. But even more affecting is the way Lydia has managed to conjure up a lost world, by patiently and intuitively reading between the lines and in the margins of the station ledgers and the hundreds of long-forgotten Victorian pot-boilers. It’s marvellous stuff.

See also Denis Welch’s feature in the Listener, this story in the local paper, and from a couple of years ago, an audio tour of the station, featuring Lydia Wevers and current station owner Ed Beetham, with interlocutor Jack Perkins. Also, Helen Heath’s lovely pics of the launch, which took place at Brancepeth itself.

--

Speaking of the earth rumbling, and books toppling: the old Trowenna Sea discussion thread has sprung to life again, in the wake of Penguin’s admission that there is to be no revised version of Witi Ihimaera's novel. Hardly surprising; everyone who is prepared to pay for a copy has already got one; there is clearly still plenty of stock to drip-feed to the bookshops; the author, recently bereaved, may not wish to revisit the material. Still, as BookieMonster forthrightly points out, it makes last year’s representations about preserving the “mana and integrity” of Te Umuroa’s story ring a little hollow.

--

Never mind. There are better books out there to spend your money and time on. This week I have been joyfully locked into Emma Donoghue’s Booker-shortlisted Room. The novel is already drowning under a tsunami of hype, but is worth the praise: it is, among many other things, a stunning depiction of the mother-child dyad, a beautifully imagined representation of how children experience the world, and a bittersweet parable of parenting -- its fierce love and its circumscribed orbit -- and the inevitable weaning and separation.

(Having known a few people who’ve found themselves living in the author's hometown of London, Ontario, I did briefly and uncharitably wonder whether the locked room also functions as a geographical allegory… Probably not, but that leads me to my favorite moment in the FAQ on Donoghue's appealingly modest website:

Q.Why did you move to Canada in 1998?

A. I once answered this question at a reading in Ontario by saying "Love", but the questioner then asked confidently, "Love of Canada?" - so I had to spell it out and say "No, love of a Canadian!"

Ah, Canadians. The New Zealanders of the north. Gotta love ’em, eh?).

Back to the book: Room is also a spectacular example of the difference between plot and story. Yes, the plot of the book is grim: a kidnapped young woman and her years in a makeshift dungeon with the child she subsequently bears. But that’s just the pretext. The story that Donoghue unfolds is vaster, larger, deeper and more humane than any of that. It’s a modest ante-chamber that opens into a labyrinth of paths; wandering them as you read will take your mind to places it’s never been before, and to some places you’ve been but have forgotten, like the numinous, luminous world of childhood, all totem and taboo and magical thinking. The very best kind of fiction.

--

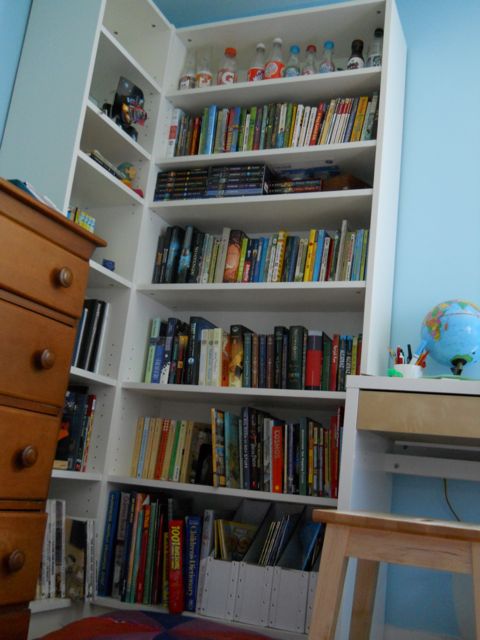

So how many books did you own when you were eight going on nine? I ask because one of this summer’s domestic tasks was to reconfigure the older child’s room -- itself about the size of the room inhabited by Donoghue’s Ma and Jack -- to accommodate his personal library. Which is currently about the size mine was when I finished grad school.

His impressive holdings are partly a function of living in a country where books are cheap. (So cheap, in fact, that when in my first semester of grad school I sat down to cover my textbooks with that sticky plastic stuff that in a more book-poor country tends to preserve their resale value, my American flatmates laughed themselves silly). When you can buy the latest hard cover Rick Riordan with just over 2 weeks’ pocket money, you can be as acquisitive as you like; the local book exchange gets a run for its money, too.

But it’s also partly a function of a dedicated collecting instinct, I think. By tripling the linear footage of shelving, we not only managed to get the various piles of books up off the floor, but also left space for future acquisitions, and -- crucially -- elbow-room for moving things around and categorizing them.

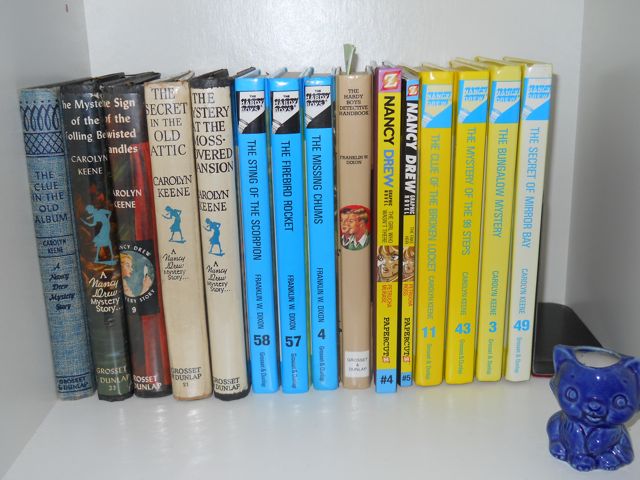

So now there’s Fiction (alphabeticised, natch) and Non-Fiction, of course, with separate sections for reference, how-to books and self-published efforts. A small collection of rare editions rivals my own prized shelf of 20th C New Zealand first editions.

There's also a magazine corner, featuring Science Illustrated; National Geographic for Kids known hereabouts as National Geographic for Babies on account of being photo-heavy and not especially full of multisyllabic scientific terms and other really hard stuff; and the splendid How It Works. (This month’s fave How It Works feature: how to mod that Nerf gun that your mother can’t quite believe she bought for you at Wal-Mart. Next I’ll be shooting wolves from a helicopter.)

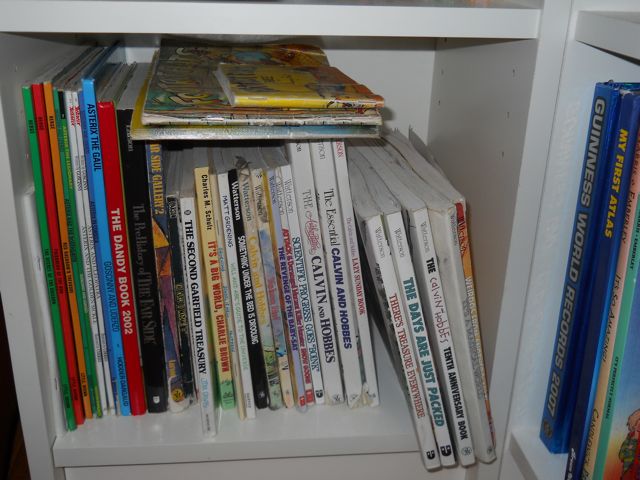

And of course the mainstay of every eight or nine year old's library: the graphic novels, especially Calvin & Hobbes, which he has entirely from memory, chapter and verse, like a good evangelist, and reads daily for inspiration and consolation.

See, too, the volumes of Footrot Flats that were a crucial part of his breakthrough to literacy -- was it only three and a half short years ago? And now it's probably a matter of months before his alphabetically-inclined four-and-a-half-year-old little brother is queueing up to borrow those same books, if he can scrape together the membership fee. Upkeep, apparently. Of the librarian's lolly stash.