Ans Westra is one of this country's most enduring and remarkable documentary photographers. A Dutch immigrant, for nearly half a century she has been photographing New Zealanders and taking snapshots of the events that form our history.

Handboek: Ans Westra Photographs runs at the Auckland Art Gallery until 15 May. There is also a beautifully-produced hardback book of the same name, which includes the images accompanying this post.

The following is a transcript of an interview between Ans and myself on 95bFM, 20 March 2005...

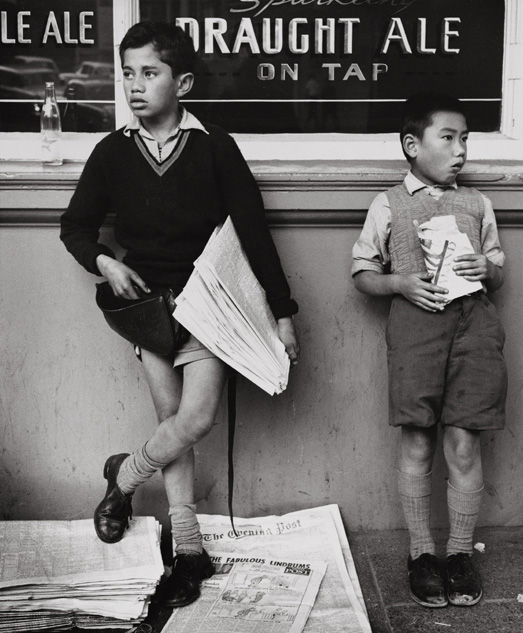

Newspaper Boy, Royal Oak tavern, Wellington 1960

So you arrived in New Zealand from Holland in 1957 and pretty much started taking photos as soon as you landed?

I had already got the camera I'm still using, a Rolleiflex, the twin lens reflex. I had already got that in Holland, I saved up for two years because I'd seen a book done by a schoolboy with that particular camera and I thought that was a nice format to go for. But my family were saying it’s a very unwieldy camera, and it's not a lady's camera, and they were against it.

It's not a lady's camera, that's an interesting idea isn't it? For those who haven't seen the camera, you shoot from the hip don't you, waist height, you look down from the top into a big viewfinder…

Yah, it is a twin lens, the top lens has got a mirror on a 45 degree angle, so you actually sort of spy on people….

It's the opposite of a periscope really, you're looking like 'down periscope'…

Yah, the down periscope. I stand around and sort of look at this little image, it's marvellous because you actually see little pictures there. Although they are mirror reversed, that's the only drawback, so you have to learn to move to the left when the image moves to the right.

We were just talking off air about shooting from down there, you said you've got the advantage because you're actually quite tall, but if you weren't, if you were my height or something you'd end up shooting some weird angles…

Yes, but there is the possibility of raising the camera, because you are looking down on an image you can actually go really low down; there are tricks of turning the camera upside down and getting on tops of crowds at demonstrations.

Aftermath, Springbok tour, Wellington 1981

Over the years you've captured images, quite well-known images, even for people who wouldn't have heard of you personally, a lot of the images would look quite familiar. Images from the Springbok tour, images from the hikoi, from Ratana, Jerusalem – you've seen a lot of our country and probably more than most New Zealanders would've seen.

I've made a point of travelling around a lot too, and some of it was on assignment, some of them were book projects that I thought of myself and worked on for lengthy periods, yah.

When you say you were on assignments, a lot of the early work you did was for the Ministry of Education, for school journals…

School publications they were called then in the sixties. I got a contact with them and I did stories for primary school, secondary school books. Yah, and that sort of took me around the country as well.

Were there a lot of well-known artists and writers working for the Ministry of Education in that sense at the time?

It was then a real hide-out for people who were really well-published authors but they needed to earn a daily crust, the books didn't give them enough income. So we had James K Baxter working there, we had Alister Campbell, we had Peter Bland, Jack Lasenby is another one that I worked closely with.

The whole atmosphere in that little office was great, it was an old building in upper Willis Street, and most of the time you found people down in the bar of the George on the corner.

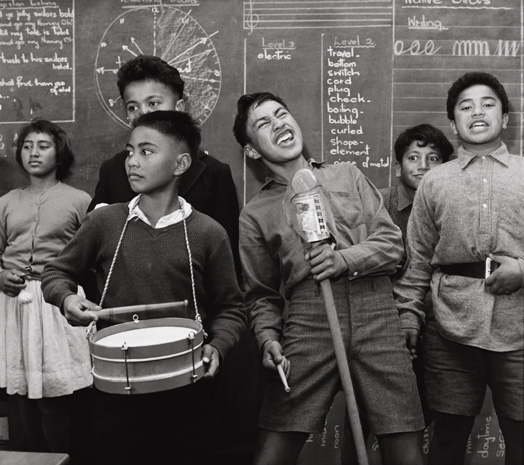

Students performing, Whatatutu primary school, near Wairoa, 1963

Would they give you the assignments to do or would you say "I'm going to go out and shoot some photos of this"?

It was a mixture; they were quite happy to have me to initiate an idea and then they would accept the work or not. But also sometimes one of them wrote a story, or some other author did a story on the freelance basis and then I would go and illustrate it, but I prefer to actually take the photos first and weave a story with the pictures.

So you wrote the stories as well?

Sometimes I did, yes.

When you went out and about, was it because of the nature of the assignments or was it because you've always been interested in people that almost all your photos – you're not a landscape photographer – it seems almost all your photos have people in them?

Well yes. Well we felt sort of up to more recently that most books about New Zealand show a very empty landscape, the people are left out. And I have an affinity with photographing people, I seem to manage to be not so noticed and not really disruptive.

How do you manage that – I mean you're a tall Dutch woman with a camera…

…Just a very quiet sort of manner and when people let me photograph them I usually sort of smile and I don't directly go and say 'thank you', and also I can't go up and say 'can I please take your photo' before I do it, because then the picture's disappeared. I've got to see the images and then I feel the reaction, and sometimes people actually notice that I might want their picture and turn away quickly, because they are shy, and then I just find somebody else to photograph.

Mongrel Mob Convention, Porirua 1982

You're probably best known in terms of your documenting Maori over the years, from the 1950s – how have you seen Maori change from the 1950s in New Zealand through to today?

Well when I came here in '57 Maori seemed to be, well, becoming very Europeanised, and that was a deliberate choice because otherwise they were handicapped economically, and if they wanted to keep their jobs they couldn't go to all the tangi and all the hui.

So I felt there was a culture that was changing, and that was not being documented because all the pictures you saw of Maori, they're aimed at the tourist market, and they're in a version of costume, but not actually how they really lived and how they experienced their own culture, and Maori were going from the land very much into the cities and the whole tribal structure was disintegrating.

But there's been a big change around because by the early 70s Maori themselves realised how much they were losing, they were losing the language for instance, and so they've really fought to retain more of their original way of life.

That whole cycle has been really interesting to document, so I did one book on Maori in the late 60s, and in the late 80s another one called Whaiora when I looked at Maori again. But I wasn't so free then to spend as much time as I could on the earlier books also, because I had a family to raise, so my strongest book is really still Maori, done with James Richie.

This version, this tourist version of Maori that you're talking about, the Rotorua sort of almost kitsch we look back at now, everyone in traditional costumes, everyone living in these stereotypical whare, those weren't the images you found when you went out…

No, I made a contract with a publication put out by the Maori Affairs Department called Te Awahau. And they covered openings of meeting houses and various events, the Ratana church gathering on the 25th of January, that's an annual thing, and we went to Ringatu meetings where no cameras had been allowed before, where they were very worried about their chants being recorded for instance, and that's only just happening now, before it all gets lost again.

Because a lot of that was just carried over verbally but because the photos were initially for this publication we had an introduction to all these things, and once I'd been on the marae, people would immediately recognise me the next time I came past, and call me in, and I could photograph at their homes, and so I built up a body of work.

Your biggest controversy in that regard was a book called Washday at the Pa, that basically for the first time showed Maori living in something other than that idealised tourist thing, that there was poverty, that there was subsistence living…

It was a real story. I knew the Education Department were looking for little stand-alone books about children in different environments, and I happened to come across, well it wasn't the first one, I did one in Tonga first, Villiami.

Washday at the Pa, 1963

I came across this Maori family on the East Coast, and they were living without electricity, without water in the house, but they were waiting for a Maori Affairs house in Gisborne to be built, so they were happy – so far as you can be happy with the circumstances they were living in. But they were not well off, they had eight children and the father was on the sickness benefit, did a bit of shearing or sorting in seasonal work. But they were such an amazing complete family, and so happy, looking after each other. Mother was baking bread, she picked up the baby when he fell over and cuddles him. I mean there was this enormous sort of warmth. And I captured that in my pictures.

They asked me in for a cup of tea and I stayed about four hours and took all the photos for the book. I went home, I had this marvellous story, because it was very picturesque, but I realised later when I had my own family how hard it must have been to raise a family in those circumstances.

And I printed the whole thing up and told the story in words, and I took it to the Education Department, and they fell for the charm of the pictures, they didn't look at how Maori would feel about it. Because once the book was out and in the schools, Maori said well, this is really the image that we try to get away from and here is the Education Department sort of romanticising a way of life that handicaps us.

Looking back do you have any regrets on putting the book out, or to you does this remain a pure story about this family?

It was a milestone in my photographing because I was so much the fly on the wall, nobody ever said "what are you doing" or reacted to me photographing even. And I re-photographed the family recently and found the same response that I could just have a free walk around.

How did they feel about the controversy?

They wanted the book back in the schools! They were very proud of being in the school book, they were not in any way handicapped by it. I mean the Maori Women's Welfare League who was instrumental in withdrawing the book, they said that the children were being victimised in the little public school in Gisborne, but that wasn't so at all. The family themselves asked me why was this whole controversy?

And now the book itself fetches hundreds and hundreds of dollars on Ebay and tradme...

Oh yes, it's quite rare (laughs)

Rebecca and brothers racing, Washday at the Pa, 1963

I mean a number of the books that you've done, you look at them and there are school journals and school publications, there's Washday at the Pa, these are books that many of us would have grown up with in our school years – I mean I went to school in the 1970s, primary school, and those books were floating around many of those.

Yes, well you can pick them up second hand, the school journals are still around, I'm sort of collecting them up now.

…they're coming back home. Handboek is basically a collection of your work over 45 years or so to go with the exhibition. What's the theme running through that?

Luit Beringer was the curator, he took it upon himself to make a selection, and he made chapters, a chapter around my Maori work in the 60s, the first marae visit, the Ratana and the first visit to a school in Parakino Pa, and beyond there the photos I took for Notes on the Country I Live In in the early 70s.

And then from there, people at work, in more recent times I've done a project around the churches in Lower Hutt and another one, it was called Behind the Curtain and it looked at prostitution before they became legalised, and I put the exhibition out there to show how ordinary their life is, looking behind the curtain.

So he made the selection from all these different projects. And then more recently the work I do in colour, there is indeed very little landscape there, but I work more on the landscape now, but more from an environmental viewpoint, on how we have the audacity to just think that because a hill belongs to us we can just cut it down and put roads through it.

Are you happy with the selections Luit made for the exhibition, are there ones were you've gone "Well, I've never liked that piece"?

Well he sort of ran it past me, he had to have a free hand initially because otherwise it became too unwieldy if we had to argue over every image. But occasionally I would say, 'Oh I think I like that one better' and he was quite happy with that, because after all I have seen the work for much longer, and I'm more familiar with it.

And he appointed five or so different curators and they all chose their own section of the body of work to look at as well. So we've got all these different people and they've written their essays which are all in this Handboek, in the publication.

Now as one of NZ's most prolific and best-known photographers, you still prefer to sleep on the mattress in the back of the station wagon just driving around taking photos, is that the way you'll continue your life?

Yes, because in that way I have that freedom, and very often people say "oh no no, you can't sleep in the back of the car, come and stay with us, but when you are staying in hotels you are in a very artificial environment, you stay in that very touristy group, and it doesn't feel like home. I'm now in a posh hotel in Auckland but I'm dying to get back in the car…

Many thanks to the Kris & the Bieringa family for providing the photographs. All images are (c) Ans Westra.