Last year, when the High Court granted Victoria University's application for an injunction against Salient, we - being the poor freeloading students that we were - went begging to the Commonwealth Press Association for a bit of dosh to help pay for the lawyers.

It was going to be a test case, we pleaded, and that media organisations needed to demonstrate that anyone attempting to use an injunction to gag the media would be ripped numerous new ones. Unfortunately, they blew all their money on TV3's fight to exclude Dunne and Anderton from the leaders' debate. The various media organisations did, however, help us rip Vic many a new ones anyway. "Payment in kind", as it were.

It's happening again. Every media outlet and their dog are jumping on Brash's injunction - and of course they have. Apart from the fact that it gives instant sex-appeal to the story ("What Don Brash doesn't want you to see!" "He'll stop at nothing to cover this up!"), they really take it personally. Media do not like people, especially politicians, seeking legal recourse to gag media - even if it's Nicky Hager, even if it's Salient. It's against their commercial interest, it's against their editorial interests, it's against their sense of justice and freedom, it's against their raison d’être, it's against every goddamn bone in their body.

They absolutely hate it, and they will spare no effort to make it really, really hurt.

But...

That's just the PR. The case is not so black and white. There is a legitimate case to be heard. I'll hand you over to Graeme Edgeler, who was our legal adviser when Salient fought Victoria University's injunction against us last year.

--

It's “Enjoined”

by Graeme Edgeler

You might think freedom of speech wasn't all that important in this country. Last year's Salient and now The Hollow Men both contained information that the authors claimed to be in the public interest, and both were enjoined from public release.

Despite appearances, getting an injunction prohibiting publication of anything in New Zealand is pretty hard, and getting one – even temporarily – without the other side having a say is even more difficult.

As with all cases where competing rights come into conflict – the rights of authors to impart information, of the public to receive it, and of senior politicians and people everywhere to privacy – courts have to weigh the importance of those rights against each other, and against the infringement of those rights that might result from any action taken. The greater a breach of privacy or breach of confidence the public dissemination of particular information entails, the greater the public interest must be in that information for it's release to be allowed.

Whilst we don't presently know the detail (and probably won't for a couple of days), we've got the gist of it – and the information sounds pretty damning. So Dr Brash wanted to stop you from seeing it? Well, no.

Getting an ex parte injunction (one where the other side isn't notified of the court action in advance) is different from run-of-the-mill contentious court proceeding. Because you're the only one there, not only do you have to make your argument and present the facts helpful to your side, you have to present the facts helpful to the other side too. You have to tell the court if you think the defendant might have a defence (like public interest, for example), and you have to provide the court with all the information you have, so the court can decide for itself the likely strength of any defence.

Don Brash will have filed an affidavit to get his injunction; it will have had to cover everything, and it would explain why he's suing John and Jane Doe (i.e. because he didn't know who had the emails). And if Don Brash did know Nicky Hager had a soon-to-be-published book, then he lied under oath. Committed perjury. Could go to prison for 7 years for doing it.

And Brendan Brown QC, his lawyer (and among NZ's top silks) would probably have signed a false certificate, and face disciplinary action before the law society. Because seeking an ex parte injunction is such an extraordinary step, the High Court Rules require a person's lawyer to take personal responsibility for it – certifying that it complies with all the requirements (like to disclose everything) and should be granted.

So Brash' injunction isn't about Nicky Hager's book. But it might affect it. Here's Scoop's copy of the injunction.

The injunction Dr Brash has obtained is against unknown defendants, described as “persons who gained unauthorised access to [Dr Brash'] computer system and took copies of email messages (“the copied emails”) stored in [Dr Brash'] computer system” or “persons who have physical possession of the copied emails or any part of them, whether in hard copy or as a record on a computer, without the consent of [Dr Brash].”

And all the prohibitions and requirements in the injunction (not to publish the emails, or to disseminate the information in them, etc.) only apply to those defendants. If the emails Nicky Hager had were leaked to him by people authorised to have them, he's fine – the injunction doesn't cover him.

It bears repeating – only in the situation where Nicky Hager (or TV3 or whomever) has emails obtained by unauthorised access to Dr Brash' computer (a crime punishable by two years' imprisonment) is he or they enjoined from doing anything.

So the injunction is rather narrower than it first seemed. Don Brash has complained about emails that were “stolen” (it's not the legally correct word, but it's a useful shorthand for criminally-obtained) from his computer, and has sought and obtained an injunction that only covers such emails (and not leaked emails, or even emails stolen in hard copy).

This distinction is important for understanding how Brash' injunction application succeeded. Successfully establishing that the privacy interest in the Leader of the Opposition's emails outweighs New Zealanders' free speech is going to be a tough ask – under the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act free speech can only be limited by the judiciary to an extent that is reasonable and can demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society. And enjoining the publication of all of Dr Brash's emails probably wouldn't cut it. Enjoining the publication of leaked emails might not have met that exacting standard. So we got this instead.

It makes some sense. Free speech isn't limitless, and limiting it in situations that arise because of pretty serious criminal behaviour – like computer hacking – is a much easier case for Dr Brash to make than limiting it where the situation merely arises because of a non-criminal behaviour ('though potentially illegal under civil law) like leaking in breach of an obligation of confidence.

Sufficient legitimate public interest in the information is still all that is needed, however, to get the information out there, no matter how it was obtained. But I'm getting a little ahead of myself – we only need worry about justifying an invasion of privacy if there actually is an invasion of privacy. Is there?

The judgment of President Gault and Justice Blanchard in the Hosking case sets out what must be established by someone alleging an invasion of privacy:

In this jurisdiction it can be said that there are two fundamental requirements for a successful claim for interference with privacy:

1. The existence of facts in respect of which there is a reasonable expectation of privacy; and

2. Publicity given to those private facts that would be considered highly offensive to an objective reasonable person."

The first bit's pretty easy. It does tell us that if Hager is just making stuff up, then he's safe – that would be defamation, not invasion of privacy. But no-one seems to be denying the existence of actual emails, or their importance. And surely it's reasonable to expect that one's password-protected inbox isn't for general public consumption.

The second limb is more problematic. On balance I think it's satisfied. It seems reasonable (subject of course to that public interest exception) that people would object to the wholesale publication of private correspondence, or even the selective publication of it. This isn't innocuous information that's being released – it comprises confidential documents intended for a very limited audience.

So it comes down to public interest. And Hager's book will meet the test. Brash obtained his injunction fearing something more personal, and perhaps more wholesale. The public clearly have an interest in evidence of criminal behaviour and deception claimed to be in the book, and that interest is a legitimate one, not prurient or salacious. Whatever it might be, The Hollow Men isn't a gossip mag outing the details of an alleged affair or detailing Brash' medical history.

Brash would still like his injunction, however. He maintains a distinction between the use of his emails (even if 'stolen', not leaked) as part of a researched political exposé and their use for other purposes. He says he'd like Hager's book to see the light of day, but still doesn't wasn't his entire inbox opened to general public scrutiny.

As a matter of law, it's a fair distinction – the public interest in Hager's book is sufficient to outweigh the breach of privacy involved in the use of information from particular politically-themed e-mails. The legitimate public interest in being able to see Don Brash' entire inbox is much less, and the privacy interest against which that interest must be weighed much greater. For Don Brash this is not a simple matter of applying to the High Court to rescind the injunction – he sees that he is protecting the privacy of all those constituents who've emailed him over his time as leader and doesn't want to let that go. Nicky Hager does not propose to breach that privacy, but without some sort of injunction it is open to others with the emails to do just that.

Nicky Hager wants to be able to publish his book, and could do that with a simple variation of the injunction. But TVNZ and TV3 and various newspapers want more: they want the injunction rescinded, and the right to publish information from any of Don Brash' emails that they have (or might get by whatever means). So even though everyone agrees this book should be out there, we might have a legal battle yet.

So how would that work?

Under the terms of the order anyone affected by it has a right to apply to the Court for new orders, and someone who falls within the definition of defendant, has a right to hearing on 24 hours' notice.

Such a hearing would likely be a rehearing of Brash' initial application. It's not like an appeal where the aggrieved party has the obligation of establishing the decision was wrong – Brash would have to establish anew that he should get the injunction – as though the ex parte injunction had never been granted.

Brash would have to establish that there is “a serious question to be tried” – that his claim for breach of privacy has some prospects of success; this would in turn require him to address whether a defence of public interest might succeed (if it would, then he doesn't have great prospects of success). Importantly, he would also need to establish that the “balance of convenience” favours the granting of an injunction – that he would suffer a loss that couldn't be remedied by monetary damages should he succeed at trial. TVNZ and TV3 probably have the money to pay damages, so that's not an issue, and monetary damages are the standard remedy in privacy cases; Brash's claim that unable to function as an MP or National Leader seems his main argument here. The balance of convenience usually won't favour prohibiting a publication, but where we're talking about the potentially thousands of emails TV3 is seeking to free up, the potential damage to Brash's privacy is pretty far-reaching.

It's a balance, so the loss Brash would suffer in the interim would need to be measured against the loss the various broadcasters would suffer if the injunction were granted and they were to succeed at trial.

This is one important way in which the Brash injunction differs from the Salient one. Brash sought the interim injunction largely to prevent the release of a book – or, as Winston Peters apparently promised, a phonebook (or was it ten phonebooks?) – of his emails while his claim that it breached his privacy awaits determination. The release of the information contained in the emails might be a supremely important matter, but (especially with no election in the offing) it's not an urgent one. Brash has a reasonably strong case that the balance of convenience lies with him. If Brash' privacy is invaded so egregiously that the public shouldn't be permitted to read a particular book (or see a particular news story) then it seems reasonable that we not get to read that book while the matter's being determined in court.

If Salient wasn't published for a week or two there'd be little point in publishing an enjoined issue at all; with the phonebook of emails Winston promised and Brash feared, or the political exposé it seems we'll actually get it, it matters less if we don't get to see it for a few months.

Nicky Hager's book will be published very shortly. No-one argues that The Hollow Men is not of sufficient public interest to outweigh any breach of privacy. If the book is what we're told it is, and the case went to trial, Brash would certainly lose (let's leave questions of defamation for another time). It's a form of political speech that is jealously protected by our laws and our courts, and no-one appears to be attacking that.

Don Brash' entire inbox is a different matter. There must be doubts that such unfettered access to criminally-obtained material (which, remember, is all Brash seeks to enjoin) can be of sufficient public interest to outweigh the serious breach of privacy involved. Brash won't retain a blanket injunction preventing all use of any criminally-obtained emails (if TVNZ has one it claims is in the public interest, it should and will be able to use it), but if Brash truly wants some sort of injunction preventing an open-slather Winston Peters' phonebook-style release of years of email correspondence, he has a good chance of getting one.

The narrow focus of the injunction – emails obtained through unauthorised (criminal) access – doesn't impose an extensive fetter on the right of New Zealanders to impart and receive information freely. A wide-ranging injunction on leaked emails wouldn't have withstood the scrutiny a full inter partes hearing would have imposed, but limited in this way – to the extent that to refuse the injunction in part legitimises criminal action – gives Brash a chance.

If he wants it.

--

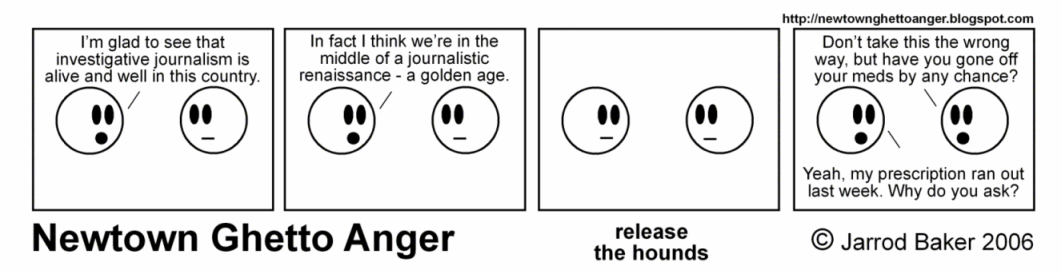

Click here for more NGA.