The Christmas of 1986, 20 years ago, was my first away from home. I had been in London for seven months and, as young New Zealanders do, I had arranged to spend the day with other Kiwis. I stayed Christmas Eve at my friend James' place on the Rockingham Estate, Elephant and Castle.

We placed our bottle each of cheap French bubbly outside on the windowsill to cool (I don't think James had a fridge). Later on in the evening, I went down to the payphone by the Duke of Wellington to make a call home.

My grandmother, my Dad's Mum, answered the phone. I greeted her cheerily, and she answered gravely. Grandpa Saulbrey, my Mum's Dad, was in hospital. He was dying, and it would be soon. I can't remember if I spoke to anyone else. I was shattered. I loved Grandpa. I hadn't expected this.

As I walked back in the gloom, I wondered what I'd do. And I decided I'd go on as planned. If Jack Saulbrey had been anything, it was a man of good cheer. I'd have a great Christmas Day and I'd drink a toast to his name.

Christmas Day, as it sometimes seems to be in London, was unseasonably mild. James and I joined the other expats at Phil and Kathleen's place and cracked our bubbly and ate special scones. Later in the day, we walked over to the Oval where there was a mad party for foreigners away from home: Kiwis, Spaniards, an excitable Italian boot girl.

But the thing I really remember is sitting down outside the Nigerian Church of the White Star, on the edge of Rockingham, and listening to the singing. It remains one of the most extraordinary things I have heard. The men set up a low, rolling chant and the women and girls shrieked and soared over the top, their voices darting like penny rockets.

That night, I caught a bus back to where I was living, out in New Cross. My English flatmates were with their families, so I had the place to myself. I turned on the gas fire, sat down and just cried. When I'd done crying, I wrote a poem. The poem has been lost somewhere, but I think it wasn't bad. The heart of it was red: red hair, red bricks, buckets of plump tomatoes.

Grandpa died on the 27th, aged 75 years. I never got to say goodbye. But I think handling it, alone on the other side of the world of the world was the first really mature thing I ever did.

I've written here before about my Saulbrey side. It's the part of me given to singing and speechifying and displays of emotion; to parties and a drink or two. You may not have come across the family name before: it's an Anglicisation. The original name was Saurbrey (sometimes Sauerbrey), and the family came from Germany via Denmark (where I still seem to have a cuzziebro) to London, where they became bakers of some note.

I'm not exactly clear when the anglicisation took place, but a bunch of Sauerbreys/Saulbreys embarked for a new life in New Zealand and Australia in the 19th century.

John Cecil Saulbrey - Jack, to all the world - was born January 13th 1911, in Aratapu, the eighth of nine children, to Thomas Lewis Saulbrey, a baker born in London, and Margaret Saulbrey (nee Dalton), born in Pukekohe. His younger sister was magnificently christened Mahala Victoria Diamantina. His older brother, Charles, enlisted in the Army, but died in 1916, before leaving New Zealand. The family was poor and moved frequently, but settled to milk someone's cows in the Hutt Valley.

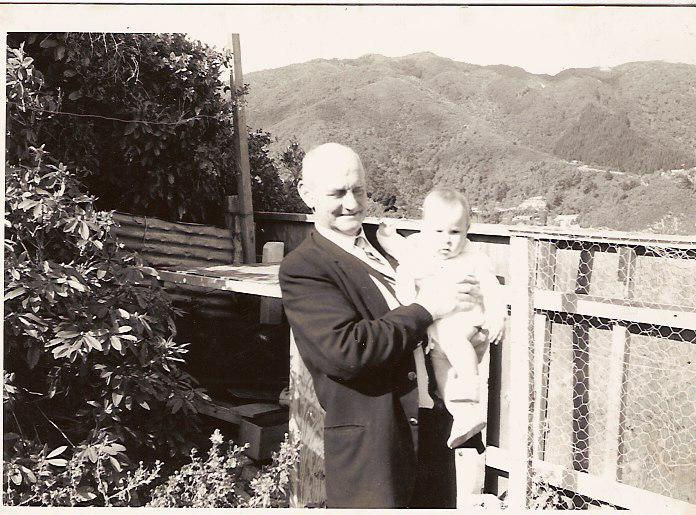

In 1927, Jack secured an apprenticeship with Hugh G. McGill, setting him off on his life's trade: bricklaying. He was well suited for the trade: a strong, broad-shouldered young man with huge hands that a brick might have disappeared into.

In 1933, he applied to join the police, presenting among other things a reference from the secretary of the Hutt Rugby Football Club, which read in part:

"Saulbrey has always impressed me as a man who is a credit to the Club and the Town, both on and off the field.

Rugby Football brings out many good qualities, and in particular tests a man's courage and his ability to keep cool in a hard game. As a member of our Senior A team. Saulbrey has proved that he possesses these necessary qualities which I know are required of a member of the Police Force.

We didn’t know this until after he was gone, and we still don't know whether he was turned down, or simply thought the better of it.

On February 9th, 1937, he married Hannah Mary Hayes at the Church of St Peter and St Paul, Lower Hutt. They lived in Point Howard and had one child, Annette (my mother) before, in 1941, he and his brothers subdivided part of the old family farm into what became Saulbrey Grove, off White's Line West in Lower Hutt. (Because he was a brickie, he was directed to join the Home Guard, rather than go off to war, and there was a sense later on that perhaps he felt deprived of the honour of fighting for his country.)

Jack was successful enough as a bricklayer to raise the finance, and skilled enough to build most of the houses in the street, including the trophy of them all, his own house, on the huge dog-leg section in the bottom of the cul de sac at No.2.

It's a remarkable house: all in double brick, with two living rooms, curved glass windows and a flat roof to allow for an upward extension that never took place.

They lived well there, with their children, Annette, Glenys, and John, and the house was a hub for the extended family. There would be frequent parties, with singing, someone on the piano, and Jack, as he would all his life, playing piano accordion. In summer, he would pile everyone onto the back of his truck and drive over to the Wairarapa for picnics. Everyone in town knew Jack Saulbrey.

Things, however, were harder than they looked. Hannah was mentally ill, and in an increasingly bad way. My mother remembers her cooking the family a roast dinner and having cheese and crackers for herself, and, increasingly frequently, being away for treatment at Ashburn Hall, the private treatment facility in Dunedin. When she was home, Jack would dilute the sedatives she had been prescribed and she would sit up in bed and smoke Craven A cigarettes. She attempted suicide twice.

Inevitably, there was stigma. My mother, as a young teller at the local bank (where she met my father), would quickly process the cheques that came through from Ashburn Hall, so no one else would see them.

On July the 29th, 1956, Hannah took her own life. She threw herself off the Hutt River bridge. My Uncle John found out in a way that will probably always trouble him. It was two days before my mother's 16th birthday, and they found her presents hidden under the bed.

There was more sadness to come. In 1959, Glenys, who suffered badly from asthma, died of an attack that probably would have been preventable today. The doctor Jack called refused to come (years later, my mother had to serve him regularly in her catering job) and they were at the gates of the hospital when Glenys passed away in his arms.

Jack took to the drink. He got together with an unpleasant woman who stole from him and whose brothers once beat him badly. People didn't come to the house so much any more. It wasn't until he found Eileen Johnston - "Johnnie" - an unpretentious, caring divorcee, who became his housekeeper, that things turned around. In 1967, he announced that Johnnie was to become his wife, and travelled to where we lived in Hamilton to tell us. (My mother, to her eternal embarrassment, didn't take the news well at first.)

This is where it starts to light up for me. I can remember visiting: the huge glasshouse strung with tomatoes; the chooks at the end of the garden, and strung in the kitchen; the rough, unfiltered rollie cigarettes; Jack bringing me raspberry and lemonades as I sat outside the Bellevue in his famous green truck (just once, I was old enough to come in and meet his mates, at the pub where he drank for 40 or 50 years). I remember the parties where people would sing the old songs, and deciding one year that I was old enough to shake his huge hand, rather than receive a kiss. He laughed and obliged.

He had a thought or two in his head, did Jack. He always spoke well of Mickey Savage, and he never forgave Harry Holland for something he said. He also - and this still intrigues me - gave me Robert A. Heinlen's libertarian sci-fi classic Stranger in a Strange Land: "I thought this might interest you," he said. It did.

Jack wasn't one to throw away paperwork, and I remember a couple of big boxes of old rugby almanacs, programmes and tour books that sat in the huge, brick double garage for years. It is one of the great regrets of my life (and I'm officially letting go of it here) that by the time I spoke to my parents after he'd passed away, they'd already been through the house and thrown that treasure away.

Jack was always very proud of the family name, which lives on through John and my brilliant cousins. And it lives on in my heart too. I never got to say goodbye, but that Christmas 20 years ago was probably the day I began to grow up. We're all a composite of our forebears, and I still feel his heritage keenly. And I guess, a grown man myself now, I'm saying goodbye this way.

Jack Saulbrey, my grandpa, was a fine man.

--

Finally, I'd just like to thank everyone involved in Public Address, and especially you, the readers. We've always enjoyed your feedback and after I finally got Public Address System to air, you turned up and made it what it is. So thanks, Merry Christmas - and look out for some interesting things in the new year.