Every time I've driven along Blockhouse Bay Road -- and, one way or another, I've been driving along it all my life -- somebody seems to be burning wet grass.

It's quite a pleasant odour; I'm not complaining or anything. But I do wonder: has it been the same person all these years? Or do the local citizens have a roster to watch for my arrival: "Here he comes now -- quick everybody, set fire to your lawn!"

All down Blockhouse Bay Hill, the pohutukawa trees were veiled in smoke. But by the time we reached the intersection with New North Road, it had begun to dissipate. Just before Cradock Street, I turned the car right, down a long driveway.

My grandfather was splitting wood on the front lawn. My grandmother emerged from the house to greet us. They both made a pleasing fuss of Bob-the-baby; declaring that their ninth great-grandchild (of ten) was even handsomer than they'd remembered.

My grandparents have lived in the same house since before I was born. As we were ushered inside, I realized how little it has changed over the years. Paintings by my grandfather decorate the walls; he designed and built most of the furniture. Everything was very clean and tidy, as it always is -- with a familiar childhood aroma of baking and fresh laundry.

While my grandmother got re-acquainted with Bob-the-baby, my grandfather showed me his latest project. For the last few weeks, he'd been struggling to complete the final draft of his memoirs. "That Microsoft Windows is bloody rubbish, isn't it?" he told me with feeling. "I should've bought a Mac."

The memoirs describe his life before emigration to New Zealand. In comparison to my Scottish relatives -- whose recollections of Glasgow's slum tenements are positively blood-curdling -- my grandfather's upbringing in Wadsley (South Yorkshire) sounds almost idyllic. Although it's now a suburb of Sheffield, Wadsley was a separate village during my grandfather's youth, and so countrified that its residents used 'thou' and 'thee' in familiar conversation (with the word 'you' reserved only for formal speech with outsiders).

The writing in the memoirs is extraordinarily vivid and entertaining. It takes talent to capture someone as skilfully as my grandfather does in this pen portrait of his own father:

I always got on well with my father. He was intelligent, good-natured, and skilled in numerous ways: a proficient artist and stone mason, excellent at blowing tree-stumps out with dynamite, and he played the concertina quite well.

The description of my grandfather's mother is nearly as colourful:

My mother was very interested in politics, and a large framed portrait of James Keir Hardie hung in our front room. If it wasn't for her family commitments, she would have joined the suffragettes and chained herself to the gates of Buckingham Palace.

My grandfather was the youngest of seven. As a child, his elder siblings doted on him: they took him on exciting excursions, and -- being talented artists and craftsmen -- made him elaborate toys. Incredibly, at the ripe old age of twelve, he was taught to drive a car by an indulgent brother. As a result, my grandfather has the hair-raising distinction of having been behind the wheel for more than 80 years.

I was interested that his memoirs made no mention of the family's experiences during the First World War. My grandfather's eldest brother was a conscientious objector -- which made things very difficult for his immediate relatives. Perhaps from habit, my grandfather skipped the answer to my question, and instead leapt directly to the defence of his brother: "It wasn't cowardice or anything with Jack, you know; he really believed that it was morally wrong to fight in that war. He was determined not to have to murder some poor German for no proper reason. Jack was gaoled, and he had a hell of a rough treatment in that prison. He stuck by his principles -- and, bloody hell, he paid dearly for them, too."

It's slightly frustrating that my grandfather's memoirs end before he leaves Yorkshire. There's a sequel still to write, in my opinion. I'd like to know more about emigration; the early years of married life with my grandmother; his time as a rigger in the RNZAF (at one stage, he played centre-forward for their football team); his art studies at Elam.

I know that my grandfather worked as a carpenter when he came to New Zealand. Two of his brothers were bricklayers; another was a plumber. Together they built a lot of houses. It must be nice for him to drive around Auckland, and to see his handiwork still providing shelter and comfort to people.

One particular aspect of his handiwork dominated my early childhood. My grandfather celebrated his retirement by building a gigantic Herreshoff H50 yacht in his back garden. The boat took five years to finish, and ripped the gearbox out of the first couple of lorries that attempted to carry it to the launching slipway. As a six-year-old, I was allowed a day off school to watch my aunt smash a bottle of champagne over its bow. It's still sailing.

We adjourned for a lunch of my grandmother's famous vegetable soup. The recipe has the important feature of being infinitely expandable -- which is highly useful if (as with her) you are the eldest in a family of fourteen children, and your younger siblings are still in the habit of dropping by unannounced at lunchtime.

If I'm completely honest, I've never managed to get my grandmother's brothers and sisters straight in my head. They are a wild tribe of Irish-Scots, with a bewildering array of nicknames: Mickey, Frankie, Joey, Jackie, Meggs, Ron, Jim, Nell, Lou, Chris, Dot, and Janice. You have to be fully inducted into their secret society to understand how 'Cecilia' could be shortened to 'Mickey', or 'Robert' could be abbreviated as 'Meggs'.

Coming from such a large (and impecunious) family, my grandmother suffered a hard childhood. To make matters worse, her family had religion. "I grew up as Brethren," my grandmother told me over lunch. "Oh, they're a miserable bunch. When I was older I switched to the Baptists because they had more fun". This astonishing statement certainly puts into perspective how fun-hating the Brethren must have been.

I wonder how many meals my grandmother has presided over in her lifetime? How many parties she's given? As a child, I can recall an endless stream of special occasions: Christmas parties, New Year parties, Guy Fawkes parties, Birthdays parties, Wedding anniversaries, parties because there hadn't been a party for a couple of weeks, and parties that spontaneously emerged out of nowhere.

The closest I've ever come to dancing properly was as a four-year-old, standing on my grandmother's feet as she waltzed around her kitchen during parties. She did her best with me, but some people are beyond unteachable. It seems a cruel quirk of evolution that I didn't inherited so much as a scrap of my grandparents' abilities on the dance floor.

Appropriately, my grandparents met at a Yorkshire Society dance. My grandfather was playing saxophone in the band. He and my grandmother had a chat, and discovered that they got along. Seventy years later they seem to be getting along just as well.

After lunch, we took Bob-the-baby for a roam around my grandparents' back garden. This part of their property has changed dramatically over the years -- becoming increasingly low-maintenance. But I found that I could still picture my grandfather's semi-built yacht, looming in the back corner. And, if I squinted, I could see the huge hedges that used to border the section: the Christmas plum tree; the kiwifruit vines; the vegetable gardens; and the chickens behind their fence.

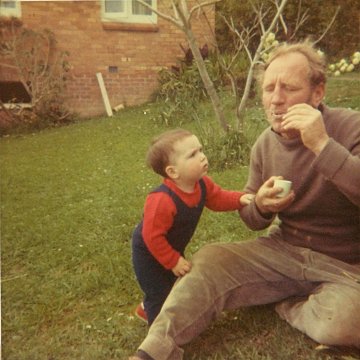

When we visited as children, my grandmother would always cut a bunch of flowers for my mother. And my grandfather would entertain me by making soap bubbles with a wire hoop.

Before we took our leave, he demonstrated that his bubble-blowing skills have not diminished over the years. Bob was utterly entranced. The bubbles shimmered in the Auckland breeze -- bobbing through the back garden, past the eaves of the house, and up into the sky.