What sort of shape is our health system in? Is it the third world cast-off that some commentators would have us believe, or is it a model of success? Sick of hearing from disgruntled patients, media reports and self-serving politicians, Dr Gareth Morgan and former treasury analyst Geoff Simmons decided to carry out their own independent study of the health system to get to the bottom of it. The study has just been published as “Health Cheque, the truth we should all know about New Zealand’s public health system”.

After spending six months carrying our more than 40 in depth interviews with doctors, specialists, administrators and researchers, I can honestly say the results surprised us.

The New Zealand public health system scrubbed up surprisingly well globally, which is a testament to the professionals involved. The real problem is that public expectations are out of control – they think it’s an “all you can eat” model. We want the latest treatments that our Australian and American cousins have, but our income is far below theirs. If the OECD average is our benchmark, we already have unmet need in NZ and it will continue to grow – higher incidence of respiratory, cancer and heart disease and markedly lower intervention rates for all three. That gap will get worse given the rising difference in incomes (& hence tax funding base) from the OECD average. In short, the public demands champagne level care on a beer budget. This is natural, because after all we don’t have to pay the bills! Meanwhile, we are competing for medical staff on an international market, and we need to match overseas salaries to attract more staff. New Zealand either needs to get rich quick or some hard calls need to be made, otherwise the cost of healthcare is going to quickly get out of control.

We need to start putting money where society gets the greatest benefit. There are some really basic things that we could do that could really improve the health of certain parts of our population, particularly the young and Maori and Pacific Islanders. We get 4 times the return from money invested in primary care and early intervention than from hospital treatments. We currently have the ambulance at the bottom of the cliff. The challenge is how to make primary care, early intervention and prevention of chronic conditions a more appealing investment to the public. Reducing obesity, perhaps by providing incentives to patients & their GPs would provide a massive return on the health budget long term for example. The attached section demonstrates the importance of making these investments in a bit more detail.

The question then arises of where the money comes from for this investment. The short answer is our health system needs to learn how to say no. We currently have a system that won't vaccinate Porirua toddlers but is happy to give a coronary bypass to a 90 year old Remuera spinster. In terms of returns to society for our health dollar, this is complete madness. We need a system that impartially draws the line where public health treatment ceases because it is too expensive to keep a person alive for too short a time. We also need to make sure people and families understand the real risks and side effects of continuing treatment, because then they might voluntarily choose to refuse treatment. We also continue to throw money at remote, inefficient provincial hospitals. These are expensive to run, provide minimal services and because few doctors want to work there they end up relying on expensive locums.

We could achieve this by having a National Health Priorities Committee led by the health profession to define the criteria for funding allocation across & within procedures. They would use an evidence-based set of criteria (like Pharmac) to deign the template for what services people can expect to receive from the health system. This would be public so that no member of the public or Press has any doubt as to why Patient A gets funding and Patient B doesn’t. This would reduce the need for local or front line discretion to be employed in deciding who gets what – the template would be set in stone until the National Health Priorities Committee meets again and changes it. Such a de-politicisation of the process is not just overdue, without it there will continue to grow inequities in the system between regions, between races, and between the ages of patients.

As evidence of the need for this de-politicisation of the prioritisation process, let’s take a closer look at what really is the relationship between prevention and cure…

- Geoff Simmons

EXTRACT BEGINS….

… from page 128-137 on primary health care….

Prevention is better than cure

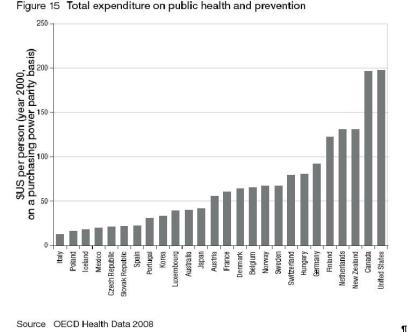

We all know the old adage – prevention is better than cure. But is it? And if it is, should we do more of it? New Zealand is already a comparatively big spender on prevention and public health, as the chart below illustrates:

Click for big version

Given it can be very difficult to evaluate the effectiveness of preventative or public health interventions, it’s politically easy to divert money away from prevention, especially when there are high-profile cases in the press of people who are dying for lack of treatment. Yet despite all the column inches devoted to the waiting lists for elective care, international evidence suggests that the real health benefits come from having a comprehensive and easy-to-access primary care system. A review of hundreds of different treatments found that preventive and primary care interventions were four times more cost-effective than procedures in the rest of the health system. Yep, you heard right – four times better value for money! US evidence also shows there are high returns from boosting the numbers of GPs and doing check-ups to pick up diseases earlier. Other literature surveys have concluded that:

better in areas with more primary care physicians; second, that people who receive care from primary care physicians are healthier; and, third, that the characteristics of primary care are associated with better health

.

So we’ve got it right when our health system spends more on prevention than most other countries, although we could do a lot more still.

******** ********

Dr Edric Baker

Dr Edric Baker is a Kiwi doctor who served as a medic in Vietnam during the conflict. There, he had the experience of working with locals in remote villages and was amazed at how well they coped in running their own care despite the total lack of modern facilities and resources. This awakened his vision of health services for the poor, by the poor. From the 1980s, Edric has devoted his life to building up a hospital in Bangladesh from scratch, training the locals in literacy and numeracy, then the basics of medical care. In 2007, they treated over 25,000 patients on a budget of $US 110,000 some of which, we’re proud to say, comes from the Morgan Family Charitable Foundation.This tale of a Kiwi hero really shows what a difference simple primary healthcare can make for a relatively small investment. One of their most important programmes works with over 200 new mothers from 14 villages each year, and tracks each child up to the age of four. Their efforts are made all the more powerful when there is a commitment to getting people to be responsible for their own care – for example Edric’s TB eradication programme is entirely run by former TB patients. It should be no surprise that these sorts of treatments figure highly in the cost-effectiveness rankings. In 2000, the World Health Organisation produced a list of the most cost-effective medical treatments. They are almost all part of primary care or public health:

• preventing and treating tuberculosis;

• family planning;

• assistance for mothers before and during childbirth;

• AIDs prevention;

• immunisation;

• tobacco control;

• treatment of STDs, malaria and childhood diseases; and health education and nutrition.

Basic public health and primary care is by far the most cost-effective way to improve life expectancy. This may seem obvious to you and me, but it is worth reminding ourselves that a large proportion of the world’s population don’t even have this level of cost-effective care.

We fund all of these treatments already in New Zealand, although as we saw with Maori immunisation rates we could do more. True citizens of the world would probably worry less about getting a new hip so they can enjoy their yachting during retirement, and more about making sure mothers and children didn’t die during childbirth in the Third World. We could easily lift the average life expectancy of the world if we closed a few hospitals in New Zealand and helped deliver basic treatment overseas. In New Zealand, around five babies die in their first year of life per 1000 live births, on average. This is a tragedy. The UN estimates that the average across the whole world is around ten times higher – 50 per 1000 live births. This is a travesty.

********

If you have a good GP, they’re likely to help you prevent developing an illness, or at least spot it early. Having a good, cheap-to-access primary system ensures most conditions get picked up early, and patients don’t go on instead to pop up later as expensive emergency cases. By this stage, treatment is very expensive and it’s often too late to do much good for the patient. Obviously, the cheaper access is, the more people – particularly poor people – will use primary care. Greater coverage means that more people get treated, and the population is generally healthier. Contrast this with the US model, where at any given moment in time, some 45 million people have no insurance. Those with insurance get the most expensive care in the world (which isn’t necessarily the best – see below) while the uninsured get nothing. The benefit (in length or quality of life) for each additional dollar spent on the rich and insured is pretty small, whereas the benefit from offering an uninsured person primary care would be immense.

There are some other reasons for favouring primary care. Specialists are pretty good at treating conditions that fall within their hitting zone, but many people have more than one condition at a time. A specialist may well overlook something that is not familiar to them, or even exaggerate the significance of something that is (a tendency that shades into the ‘supplier-induced demand’ we will discuss in the next chapter). GPs, by contrast, are more likely to take a holistic approach to your care and treatment, and as the gatekeepers to the health system, they may even save you from yourself when you show up waving a printout from www.hypochondria.com and demanding treatment that is, from an expert perspective, unnecessary. A good GP or practice nurse can hold our hand and talk us down from our fear of the radiation from our microwave, or our fixation with the symptoms of whatever disease we’ve convinced ourselves we’re afflicted by.

You may think the US model – where patients are passed from one specialist to another and subjected to a barrage of tests – is superior, in that it’s better to be 100% safe than sorry. But American outcomes don’t support this. It turns out that 95% certainty is an acceptable trade-off, given that we avoid all manner of unnecessary tests and procedures at the hands of overenthusiastic specialists. This actually helps our health because, surprising as it may seem, medical treatments carry a medical risk too. Medical treatments themselves are the third biggest killer in the United States, behind heart disease and cancer.

******** Who guards the guardians?

A group of US doctors were given the following scenario. A forty-year old woman presents with chest pain after a fight with her husband. A check of her heart rate shows it is normal. The chest pain goes away. She has no family history of heart disease.The doctors were asked what they would have done fifteen years ago, and what they would do now?

What gets funded?Fifteen years ago, they would have sent her home. Maybe she would get a stress test (they would measure her heart rate during light exercise, for example, like walking on a treadmill) to confirm that there’s no issue, but even that would probably have been regarded as overkill. But today, the cardiologist said, she would get a stress test, an echocardiogram, a mobile heart rate monitor, and maybe even a cardiac catheterization (sticking a tube up a vein or artery to test blood flow around the heart). The last carries a risk of death. No wonder healthcare costs have ballooned over the years.

********

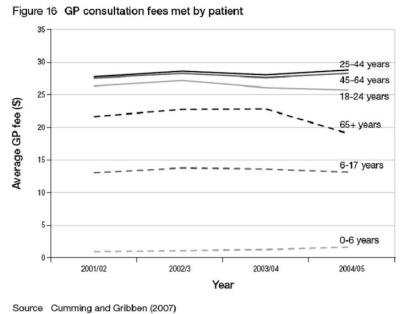

Prevention, then, is better than cure, and the effectiveness of spending in the areas of public health and primary care proves it. It’s a big thumbs-up to the fifth Labour-led Government, too, which in the early 2000s channelled huge amounts of money into primary care. Their aim was to get primary care – GPs, nurses, physios, pharmacists – working together with their local community in a much more preemptive capacity. Prior to their reforms, GPs were paid for each patient visit, so the sicker a person was, the more the GP saw them and the more money they made. There wasn’t much of an incentive to get patients to take care of themselves. Labour changed the system so that the payment to PHOs (who operate on behalf of GPs) was based on each patient they have enrolled, rather than per consultation. The idea was that this would shift the focus to prevention. Labour also increased the funding significantly in order to reduce the co-payment made by patients, in an effort to improve access. As shown in Figure 16, the average levels of fees have stayed roughly stable since 2000, which amounts to a fall in real terms.

Labour rolled out its increased funding to certain age ranges and groups over several years, and it only extended to cover the whole population in 2007, so the full effects have not yet been evaluated. But on the basis of their earlier increases, the funding led to lower fees and greater use of primary care (particularly for the elderly), though not, it seems, by as much as the additional funding. Their initial target areas were poor neighbourhoods, especially with high Maori and Pacific Island populations. In these areas, Labour achieved their goal of reducing fees to zero for children, $7-10 for ages 6-17 and $15-20 for adults. But in other, more affluent areas, they were seeking fee reductions for those aged 65 and over (without a Community Services Card) of $26, and average fees only fell by a paltry $12. These initial signs are worrying – over half of the new funding in affluent areas seems to have gone straight into the GPs’ back pocket. There’s some potential benefit – after all, we need to attract new GPs to the sector – but if affordable care can be delivered in poor areas, you have to wonder why it’s not being delivered in richer areas, too. We will shortly explore how many GP practices in affluent areas may be operating inefficiently, and how Labour’s cash injection may simply be prolonging their demise.

Click for big version

Other, early signs of the impact of Labour’s reforms give rise to cautious optimism, but not much more than that. On average, people are seeing their GP more, particularly the over-65 year olds, who as a group visit the doctor 25% more than they used to – after all, it’s now cheaper than calling an 0900 clairvoyant number for a chat. The extra cash has significantly reduced the proportion of people who can’t access a GP because of cost – this has fallen from 4% (in 1996/7) to 0.8% (in 2006/7) for children and from 6.3% to 1.8% for adults. However, the ultimate measure for improved prevention is a reduction in preventable emergency admissions to hospital, and these haven’t yet shown a significant, sustained fall. Have the reforms encouraged primary care providers to practise preventive medicine, as it was hoped they would? In fact, there’s reason to believe they have not, as we’ll shortly see. Labour’s dream was to realise Mickey Savage’s vision of universal free (or low-cost) GP care. With many GPs taking a cut from any funding increases, this now seems an increasingly unaffordable goal.

How far do we go down the road of preventive medicine? There’s considerable and mounting evidence, for example, that early childhood experiences (such as developing a loving bond with a mother) can have a positive impact on a lifetime’s worth of health outcomes, as well as other positive stuff such, as reduced crime.107 Evidence suggests that help to improve the mother-infant relationship targeted at young mums in high-risk communities can have a social payback of $6 for every $1 invested. Other successful programmes have used pre-school education to reach parents and children. Such investments are difficult to evaluate, and at any rate, it takes many years before the benefits are known.

This kind of preventive medicine shades into the realm of social care. Health and well-being has been shown to be correlated with indicators from many other areas of life, especially education, housing and employment. Counties Manukau DHB has piloted a programme that helps mental health patients deal with these and other issues. This pilot led to a dramatic reduction in inpatient admissions, and proved a cost-effective investment overall. But is this really the responsibility of the health service, or is it picking up the pieces for other failing public sector agencies? Does it indicate that it’s unhelpful to have the agencies that extend help to people in need – whether it be medical or social – working in silos? Do we need to develop a more holistic approach to the whole gamut of state-provided assistance?

All this talk of the value of preventative medicine obscures another important point. Increasing investment in prevention or primary care – as the Labour-led Government did in the 2000s – is unlikely to reduce the burden of elective surgery needs on the health system.110 This may come as a surprise – that the barrier at the top of the cliff doesn’t reduce the need for the ambulance at the bottom – but it stands to reason if you think about it. The fact of the matter is that we’re all going to fall off the cliff at some stage. All primary and preventive care does is extend our healthy lifespan, delaying the inevitable, as it were. If we’re putting our money into preventive and primary healthcare, does this mean we ought to be grateful for the increase in our healthy lifespan, even as we accept that resources have been diverted away from the system that will address our needs when that healthy lifespan nears its end? It probably does, but that’s almost certainly not the way it will work. We’ll grab with both hands the extended, healthy lifespan all that investment in primary care and prevention offers, and then bitch like crazy about the lack of resourcing of elective surgery when we reach the point when we’re relying on it. And in the absence of informed debate on the subject, the government will (on past form) rush to oil the squeaky wheel.

That brings us back to the question with which we opened this chapter. Do we want a health system that maximises our healthy lifespan on the basis of need and ability to benefit (regardless of the ability to pay)? Or do we want to make sure our parents get gold-plated service on the way out? Based on the assumption that a year of life of each citizen is of equivalent value (and so the lives of the young are generally worth more than the lives of the elderly), then in terms of the value per dollar, it’s a no-brainer. But clearly the good folks of Remuera and Roseneath don’t quite see it that way as they face the final curtain.

EXTRACT ENDS….

The book Health Cheque is available to be purchased at www.healthcheque.co.nz