I've written before that my grandfather's autobiography was on the verge of completion, but the final steps to publication have taken rather longer than expected. Like many writers, my grandfather felt that he needed to make a few minor tweaks before his masterpiece was ready to be released into the world. And then each minor tweak seemed to beget a whole family of additional tweaks. And so on.

Towards the end of last year, my grandmother began to issue hints. She is a good-natured woman, who once endured five years while my grandfather built an ocean-going yacht in their back garden. But patience has its limits, and she was keen to see his autobiography finished and printed in book form. In fact, she had rather hoped that it might be out for last Christmas -- although, in the end, a few of those essential tweaks prevented this from happening.

By January this year, my grandmother's hints had become more forceful. Eventually my aunt's support was enlisted, and she prised the autobiography from my grandfather's unwilling hands, and emailed the manuscript to me for typesetting and cover design. The lay-out was undertaken at top speed (or, at least, top speed in comparison to the glacial rate at which I normally work), and the book was duly sent off to the US for printing.

Alas the printing process introduced yet another maddening delay. The proof copy of the autobiography had to be posted back to New Zealand for final approval, which meant that we'd be twiddling our thumbs for nearly a month while the book dawdled its way to our shores, or more likely, while it was sent to Canada by mistake.

It was then I discovered that requests issued by grandmothers are still effective in other hemispheres, and indeed, even to persons not related by blood. A certain Dr Jolisa Gracewood was dragooned into our mission. We decided that the book should be sent to her lair in Connecticut for final checking, thus saving three-and-a-half weeks on delivery of the finished product to my grandparents in Auckland.

At this point I can predict, of course, what anyone who knows of Dr Gracewood will be thinking -- viz. the woman is a monster, she'd never acquiesce to helping somebody's grandmother.

Well, I like to think there's goodness in everyone, even Jolisa Gracewood. And, indeed, my faith in humanity was rewarded. She agreed to do the job, and not only that, but she rearranged her busy schedule to check the proof copy on our behalf the very day it arrived. And, as if that wasn't saintly enough, she on-posted the book to my grandparents via priority mail, and wouldn't hear of being reimbursed for the cost.

So take that -- all you people who have so often compared Jolisa Gracewood with Mussolini or Simon Cowell! Hang your heads in shame. She's nowhere near as thoroughly wicked as everyone says.

At any rate, thanks to Dr Gracewood's good work, the proof copy arrived rather earlier than expected -- and great was the rejoicing! My grandmother was moved to tears to see my grandfather's autobiography finally finished; and then moved to tears again when she discovered that he'd dedicated it to her. My grandfather exhibited his pleasure in the manner of Yorkshiremen everywhere, with my aunt's highly-trained eye being able to detect a brief hint of a smile.

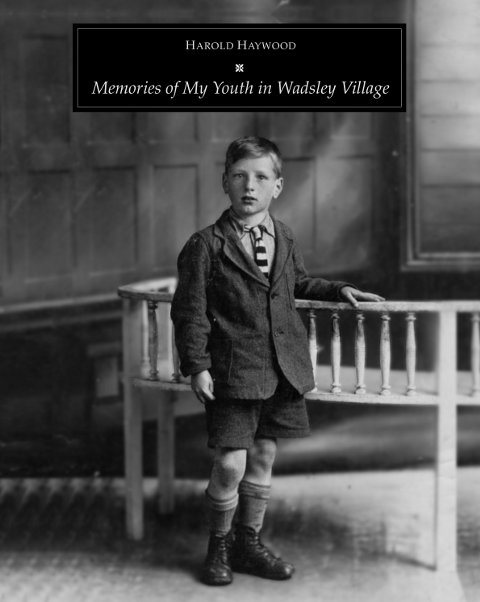

Above: The cover of my grandfather's autobiography (featuring a photograph of him as a six-year-old).

It has been my experience -- to make a gross generalization -- that Yorkshiremen are rather inward-looking in terms of their world-view (certainly few Yorkshiremen would be surprised to read the headline: "Cosmologists Calculate Yorkshire is at Centre of Universe"). It's lovely how my grandfather manages to make a virtue of this in his writing, taking the reader into the minutiae of village life: the local school, the market, the cottages, and the mines. He makes some wonderfully wry observations, as in this brief mention of the Wadsley village allotments: "A place where the men had a little shed, talked to one another, and got away from their Yorkshire wives."

Above: A map of Europe from my grandfather's book (showing all the important European landmarks).

Given that most of the book takes place during the hard years of the Depression, it's a surprisingly sunny autobiography -- with prose that often captures the sense of joy or yearning that arises from happy childhood memories (typically the Germans have just the right word for this: Sehnsucht). My grandfather recalls the first day he was able to go outside after a prolonged childhood illness:

I went by Bower Cottage, to a field past the bottom pit, and sat down on a large rock in the warm sunshine. I had not been there long when I saw a skylark come out of the grass and start to ascend into the blue sky. It hovered there for a little while and then burst into such a beautiful song -- as though it went so high just to sing to me. I have never forgotten it.

There is sorrow in the book, too -- much of it in the telling of his father's (my great-grandfather's) life. Joseph Haywood was the second eldest in a family of five children. His older brother Walter died at the age of four; shortly afterwards Joseph's mother and youngest brother also died. Then his second-youngest brother John (also at the age of four). Finally his father died, leaving Joseph as a ten-year-old with his little brother, Harry, to be employed as child-labourers on the farm of an obscure relative.

By hard work, Joseph and Harry clawed their way upwards in society, educating themselves in their spare time, and eventually studying at mining school in Sheffield. They mined ganister for a local company, and became relatively prosperous, establishing their sons as tradesmen. If you've never heard of it, ganister is a natural form of almost pure silica, used to make the linings for furnaces. It's the sort of material you get chaps in space-suits to deal with nowadays because of the danger of silicosis. You can imagine how it ended for my great-grandfather and his brother.

Above: My grandfather's father as a teenager.

For members of the Haywood family there are a good few surprises in the book. My grandfather's great-grandfather had the surname 'Heward' -- but most of his children had their surname spelt as 'Haywood' (excepting one who was 'Heywood'). So the ancient House of Haywood is not really so ancient after all, and owes its existence purely to a freak of spelling.

Most importantly, of course, was the discovery that my grandfather and his brothers -- Harold, Horace, and Hubert -- didn't draw the shortest straws when names were issued in the Haywood family. That honour went to their great-grand-aunts: Keziah, Uriah, and Hephzibah.

The autobiography ends with my grandfather meeting my grandmother. He was a musician in a dance band at the time:

I played the saxophone with the band that night, and in came this slim young lady with long auburn hair. I walked home with her that evening and little thought that I had found my mate, and that we would be together more than seventy years later.

Above: My grandmother in 1943 (four years after she met my grandfather).

In many ways, I think I've been more excited about this book than either of my own. My grandfather phoned me the other day, when the boxes from the printers finally arrived at his house. He also had some bad news to deliver: my grandmother had been suffering from a chest infection, and was required to spend a night in hospital under observation. "I don't want to open the boxes without her," he said. "So I'll wait until I can drive her home this afternoon." Later he emailed me photographs of my grandmother surrounded by autobiographies.

I flew up to Auckland that weekend to attend a book-launch party that my aunt had arranged. My father and his wife collected me from the airport. "Grandma's not going to be there, I'm afraid," my father told me. "She's had to go back into hospital -- they think it might be pneumonia."

The book-launch was delightful -- if somewhat subdued as a result of my grandmother's absence. My brother and sister were in attendance, as were my cousins, and nearly all of my grandparents' great-grandchildren. The great-grandchildren were running wild on the delicious sugary food that my aunt had cooked up.

Surrounded by relatives, I had time to reflect once again on the cruel quirk of genetics that has resulted in my missing out on the Haywood hair gene. My grandfather -- aged 93 -- has not a trace of grey in his hair, nor does my aunt or her children. It's nothing short of a scandal, in my opinion, that a grandfather should have less grey hair than his own grandson (and possibly thicker hair, too).

Above: My grandfather signs a copy of his book.

During the course of the proceedings, it became apparent that my grandfather had been keeping back some bad news. He hadn't wanted to ruin the party. During the night my grandmother had suffered a stroke.

We visited the hospital that evening: my brother, my sister and her husband, and me. It's surprising what people think about in such circumstances. In spite of her difficulty in breathing and her paralysis, my grandmother's first question was about the welfare of my grandfather.

"Is someone organizing his clothes?" she asked. She's never held my grandfather's fashion sense in high regard, and for the last seventy years has been making sure that his clothes match properly. "Remind him that he's got a new packet of underwear in his drawer."

We told her about the book-launch. My grandmother soon became tired; her speech difficult to understand. Several times we couldn't make out what she was trying to say.

My father and his wife arrived. We talked about childhood visits to my grandparents' house. I recalled how -- knowing my dislike of meat -- my grandmother had always made me her special vegetarian soup. "We had your vegetarian soup at the book-launch party," I was able to tell her. "It was very good, although not as nice as when you make it."

"That's because Grandma's vegetarian soup is made with shin-bones," said my father.

We had to leave soon afterwards; it was hard to know what to say in farewell. "I'm sorry to see you so ill," I told my grandmother.

She seemed able to speak more clearly again. "It's all just part of life, isn't it?" she whispered.

I only hope that -- under similar circumstances -- I can be as brave as her.

My grandmother, Cecilia May Haywood, died at 3 pm, 28th May 2010. She will be sorely missed.